Disclaimer: this knife was supplied at no cost by Spyderco as part of their brand ambassador program. The review that follows, however, remains entirely independent and unbiased. I thank them for placing their trust in this little blog.

Paul Alexander is back, and the COBOL is perhaps his most aggressive creation yet. Built on the “techno-primitive” DNA of the NAND™, this knife isn’t just a tool—it’s an alien in your hand, standing out even in Spyderco’s lineup, which is renowned for pushing the boundaries of design.

No real lock, just a generous choil. The purpose? A steak knife? An impact tool? Or could this be Spyderco’s very first letter opener?

The blade geometry is thick, so it’s no whittler—but you could still sharpen a pencil. Or maybe… it’s a paper knife after all.

(Paper knife vs. letter opener—often confused, but they are not the same. Paper knives were made to slice open the folded edges of hand-produced books before reading. Letter openers grew out of them: longer, blunter, and built solely to tackle envelopes. Today, paper knives are mostly collectibles, while letter openers remain a staple on desks everywhere. They come in wood, metals like stainless steel, silver, or pewter, plastic, ivory, or mixed materials—often with decorative handles stealing the spotlight. Some modern designs hide a retractable razor, and electric models can blast through stacks of mail—but beware: they can nick the contents.)

But the COBOL blade explodes with a hybrid of Japanese tanto elegance and katana-inspired Americanized assassination tool, machined from M390 particle metallurgy stainless steel. Its saber-ground primary bevel flows into a saber flat grind at a faceted tip, ready to slice with surgical accuracy.

It is an eye candy ! Even closed.

The handle is crafted from titanium for a sleek, minimalist look. Integral spring arms and seated ball bearings do NOT lock the blade, but a generous choil and thumb pressure on the tail keep every grip surprisingly secure. A hole in the handle aligns perfectly with the signature hole in the blade, completing the design’s clean, purposeful aesthetic.

Made in Italy, this Japanese‑inspired blade oozes quality — but don’t expect buttery action. It’s slow to open and even harder to close. Think of it as a straight razor: there’s no lock, so safe handling is essential. You actually grip it by the blade, a move that recalls antique Roman folders rather than modern folders with locking mechanisms.

Flip it open one-handed using the extended “tail”—don’t expect the thrill of a straight razor snapping into action. It’s slow.

But once open, you can admire the clash of techno-primitive design with katana-inspired elegance. In the right hands—and with the right mindset—it’s more than a letter opener; it could be a self-defense tool. After all, geishas once defended themselves with hidden blades…

A gorgeous showpiece that’s too long for UK carry rules. Opened, it goes from elegant to downright threatening.

Compared to one of Spyderco’s top EDCs, the Sage 5 Salt, the COBOL takes on a far more menacing presence. Where the Sage 5 is sleek and understated, the COBOL commands attention—its techno-primitive, katana-inspired lines give it a dangerous edge that’s impossible to ignore.

Another beautiful desk knife in my collection: the Pole Position. Desk knives, made for opening letters, are more than tools—they’re elegant objects, carefully designed and treasured by collectors.

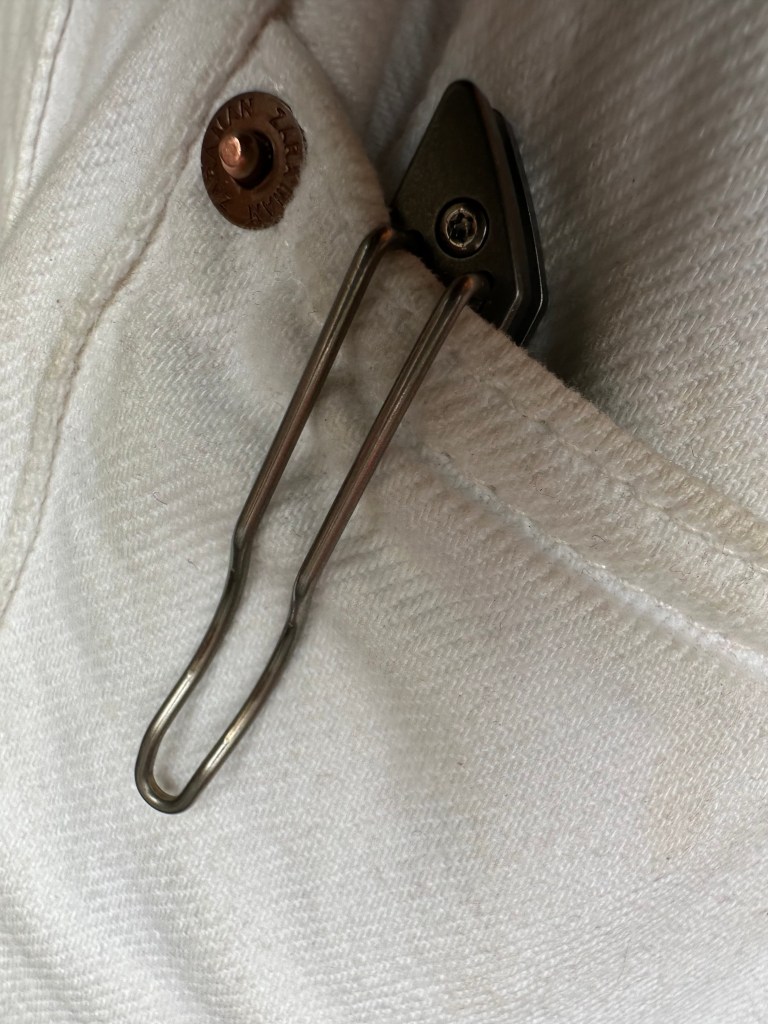

Ambidextrous, the COBOL comes with a reversible deep-pocket wire clip for left- or right-side, tip-up carry.

So, who is the COBOL for?

Out of the box, mine won’t shave—it could use a thinner edge for my taste. It is sharp but razor not sharp.

The flipping action is also really slow, but once open, you’re holding a stunning object, perfect for a desk: cutting strings, opening letters, small chores. Using it in the woods? Forget it. In the kitchen? Its geometry isn’t ideal. But as a steak knife? On the plate, it would certainly shine.

Tried the COBOL on some wood—ouch! To keep control, you’ve got to brace your index on the choil, since there’s effectively no lock. That makes it tricky and dangerously easy to catch the blade’s heel, even half open, just to avoid a jump close. Bottom line: this knife was never meant for whittling anything.

So, really, the Cobol is from another world—an alien and a looker. And yet, loving this alien is easy. The craftsmanship is impeccable: titanium engineered with clever CQC design, every detail thoughtfully executed. But it demands a place of its own. On your desk, at the table or in your collection, the COBOL isn’t just a Spyderco knife—it’s an extraterrestrial in their production. Spyderco is known for their high performance knives. Yep, in that matter this beautiful one is something from another mind.

But now, if you love the alien, it’s up to you to decide how you’ll use it — but with such a very soft locking mechanism, be mindful of its limits.

Here is the link to Guillaume’s Cobol review.